Weltformat Symposium 2021

Talk and panel delivered with Evening Class in section of the 2021 Weltformat symposium entitled ‘Care and graphic design’, transcribed below.

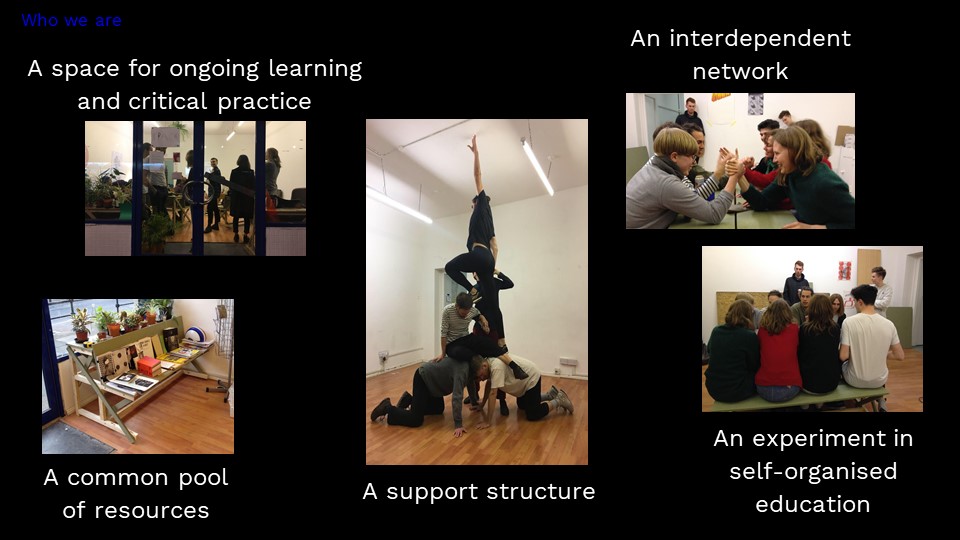

Hello, my name is Andrew and I’m here with Dina and Wouter on behalf of Evening Class. We were supposed to also be joined by Jeanne but she sadly couldn’t make it due to a COVID travel issue. By way of introduction, Evening Class is a self-organised education group of 15 members based in London, but with participants based around Europe. Today we’d like to talk about care and design education, and the different relationships self-organised groups might have to care compared to institutional alternatives like schools and universities.

We wanted to preface this talk by saying that our views are not necessarily the views of everyone in Evening Class, and that we come at this from a mostly UK centric perspective, as this is the site of most of our investigations into both education and the design industry. Whilst our work revolves around topics of care, and is often a response to what we see as a lack of care, we want to stress that we don’t see ourselves as care experts in any way.

To set the scene, the UK has the most expensive post-school education in Europe. Undergraduate studies cost around £9000 or 12000CHF per year. It is estimated that throughout their studies, students will accrue so much debt that most will be repaying for the rest of their working lives.

Students who complete their undergraduate degree will find there is limited funding for Masters studies, and this can be dependent on which subject you choose, your age, and your nationality or residency status. Even for those who are eligible, the loan will barely cover course fees, so those without savings or those unable to live with family may find themselves excluded. Those with caring responsibilities have reported finding it particularly difficult to get the support they need to study.

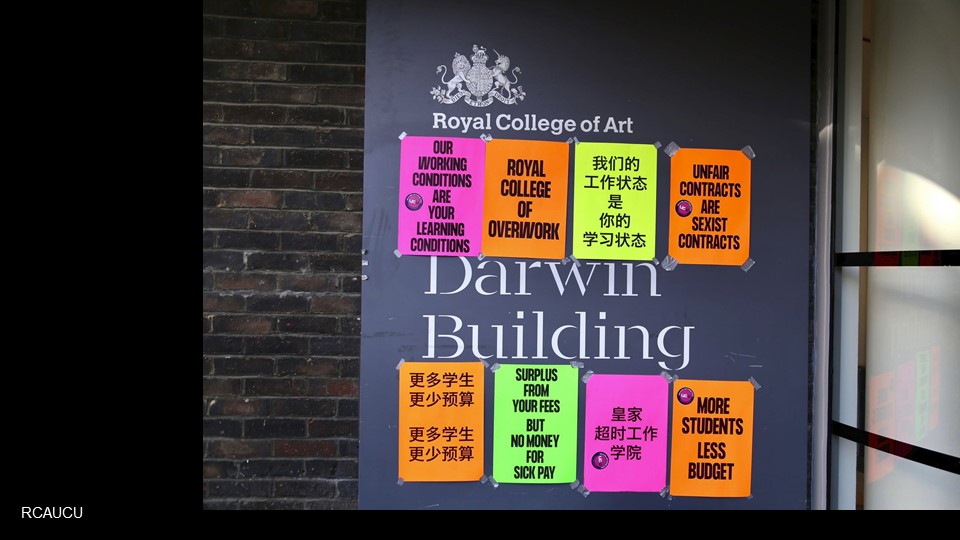

For those who can access education, a range of grievances might emerge. Education and industry work in tandem to reproduce many of design’s ugly traits. Some of these are displayed here, reported in various Evening Class discussions and workshops about our participants’ experiences.

From the outset, students may experience intense encouragement to compete against their peers for what they are told is a limited pool of desirable jobs. Part of this competition may include encouragement to take on unpaid internships or placements. Evidence suggests women and people of colour are more likely to end up in unpaid work, and when they are there, are more likely to find themselves appointed with non-design tasks. This pressure sits uncomfortably alongside institutions’ corporate wellness frameworks, encouraging students to deal with the stresses of education by exercising more, attending resilience workshops, and using under resourced mental health assistance.

In the UK, the lack of care has been striking in some universities’ responses to covid – forcing students to pay full fees despite no access to studios, students forced into paying for unused accommodation, and in one case fencing students into their accommodation blocks.

University staff can feel different pressures – precarious contracts, late payments, unreasonable workload, discrimination, just to start. The image is from an ongoing strike at the Royal college of art, organised by the university and college union.

There is also an imbalance in the way academic staff and support staff are treated – universities often set themselves targets to be living wage employers, meaning they pay everyone a basic minimum wage, but then outsource cleaning or security to save costs – a way of hiding low wages. This is often heavily racialized, with these roles commonly filled by migrant workers.

Evening class was born as a response to these frustrations and also because of a lack of existing options outside of university led education. Evening Class was set up in Jan 2016 by two members with an open call. Everyone who responded eventually joined, and for a few years we had regular meetings twice a week. Our symbol is a bat, as we were mostly working outside of working hours, mostly at night.

Members came for different reasons: for many it was an affordable alternative to higher education, for others a community and support structure in their design practice. Many of the initial members have since left but evening class still remains open for new members.

Our program was decided democratically, sometimes by vote and sometimes by rotating curators. For the first few years we had a studio space in a shop front in East London, where we held our biweekly meetings as well as public events. We were inviting guest speakers and organising public discussions on the realities of the design industry and education. We also held a number of workshops both at our space, in universities, and at design events. These workshops mostly focussed on consciousness raising and collaboratively exploring alternatives to the studio design model. We held number of reading groups, which gave us shared references, and we also held social fun events like walks, talks, dinners and parties.

Throughout the course of the classes, the issues we explored have often led to a desire to create practical outcomes. The first of these was the open letter to the major job boards that advertise jobs without disclosing the salaries – AKA salary cloaking.

> Wouter reads

‘Dependent on experience’, ‘Competitive’, ‘To be confirmed’, ‘Negotiable’.

‘Dependent on experience’ implies that the applicant’s level of experience will be evaluated and validated by the employer, a valuation that is not transparent and never explained by an employer who’s judgment is based not just on what you achieved, but on a set of assumptions surrounding f.i. what university you attended.

‘Competitive’ is a peculiar proposition, given the widespread lack of salary transparency. Is this competitiveness pegged to your cost of living? Or based on your personal level of wealth? Or on whether you support or care for other people in your life? Or, is it simply wildly flexible and subjective?

‘Competitive’ also alludes to the prevalent atmosphere within today’s increasingly insecure work environments, and candidates are being tacitly encouraged to undercut one another, and to be in opposition to your peers becomes common practice.

‘To be confirmed’: how long does one need? How convenient for the employer that confirmation of salary can come at the end of the interview process. The question arises: why are employers listing jobs when they don’t know what they can afford to pay?

‘Negotiable’ is insidious, as it suggests a rebalancing of power is possible, with the prospective employee being able to push for a higher salary. Graduates just out of university should not be expected to be experienced enough to be able to ‘negotiate’ a fair wage.

This open letter been co-signed by may of our collaborators and you can help with signing and sharing it. We also keep all the resonances from the job boards public.

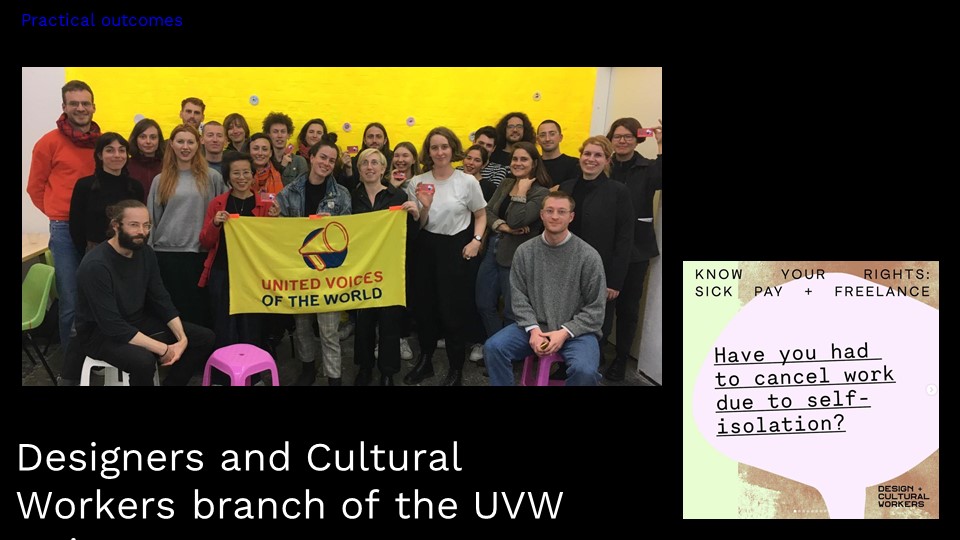

A more recent practical response to conditions in the design industry was a subsection of Evening Class setting up the designers and cultural workers branch of the United Voices of the World union. This project started with a small research group looking at the history of unions in design and led the group starting their own branch of an existing union. UVW is a UK based union which represents precarious workers from a number of sectors including cleaners, caterers, and sex workers. The designers and cultural workers section is a place for all people who are involved in cultural production, including office staff, cleaners, and other support workers. As well as protecting its members with legal advice and support, the union produces publicly available materials to help educate design sector workers on their rights. These materials could be also helpful for designers outside the UK who unfortunately can’t benefit from the legal support of the union.

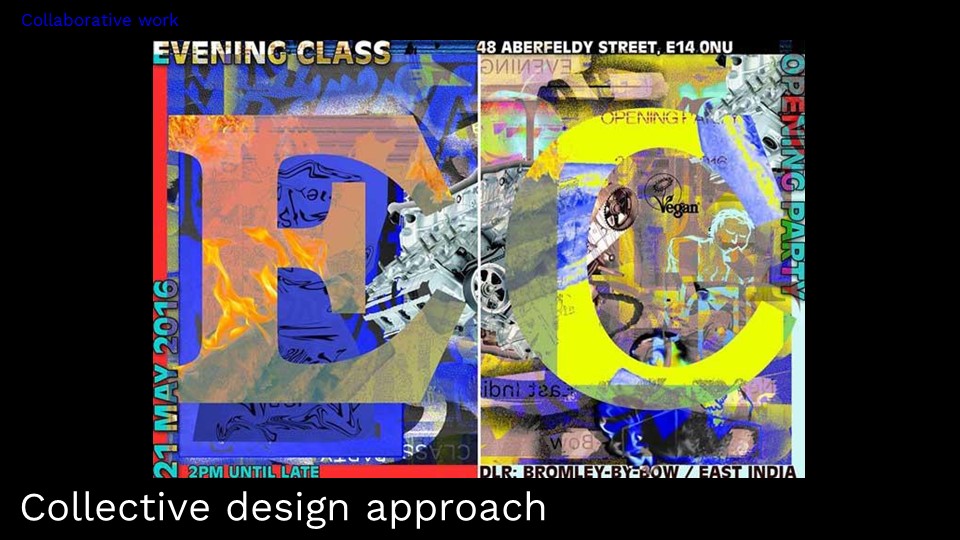

We often experiment with how to represent different voices of EC members into our work. In 2016 we were approached by the Precarious Workers Brigade to design their book ‘Training for Exploitation’ – a toolkit with resources and exercises for young graduates in the cultural sector aiming to help them avoid being exploited upon graduation. This was our first project that we designed as a large group, we also made a short contribution to the book about the design process.

> Wouter reads:

But how do twenty-plus individuals begin to work on something like this ? How can we remain non-hierarchical when decisions need to be made and deadlines met ? In the embryonic stages of any project, much of the work manifests as discussion and sharing of ideas – almost so much that there is no end in sight (or in this case, a start …). 2 An early suggestion was to split into groups to complete individual sections, with each one working under a different political condition, ie dictatorship, communism, etc. Another was to make oblique reference to our labour by including a commentary in the margins throughout. 3 Another was for groups to continually pass on the working document, refining – or sabotaging – the work from the previous group, with little regard to having a coherent visual style. The book would need to be functional, though, so the eclectic collage of styles would have to be ‘reigned in’ somehow. As interesting as all of these methods were, the need to cease thinking and begin designing had reached breaking point, so we forced ourselves to settle on a system of ‘Anarchy in Action’ 4 : two or more people would work on the book during pre-allocated time slots at our studio space, with remote working allowed. In an attempt to remain col- laborative, we also decided that no one should work on the design alone. Groups of indi- viduals would clock in and out, annotating decisions made and calculating the amount of hours spent working on each page, and so on. In theory, it was a workable system but problems soon emerged. The nature of working within pre-determined slots resulted in those who had more free time or a flexible working day being able to spend more time shaping the design. Not surprisingly, some of those who work full time did not warm to the prospect of working in the evening, after work, in order to offer their input. Also, group working often became one person in control of a laptop with a dozen backseat art directors, which was – apart from being an amusing scenario – a wasteful use of our resources as a group. There was also an issue of people feeling a lack of ownership of the project, which may have been because they had been away (the bulk of work was done over the summer holiday), or because they felt that they should not pick up (or criticise) where others, who were seemingly more informed about what needed to be done, had left off. In other words, it is only because we allowed our system to break, and released ourselves from the restrictions we forced on ourselves, that the finished book is now in the hands of the reader. Despite these difficulties, working together in this way has been a worthwhile step for us in testing out alternatives to how we have so often worked – individually – in the profes- sions of art, design and education. We hope the final design reflects our continuing efforts in working collaboratively, and also that sharing these experiences and learning from them can encourage and empower others to do the same.

Another example of this experimentation is this Party flyer from 2018. We developed this pretty chaotic approach of making quick collaborative design work that we often use. Each member spends just 10 min on design, changing or adding one element, and passes it on to the next member.

This is another example of how we integrated many different voices into the design, but different voices of the client. In 2018 La Foresta invited us to design their visual identity. They are a community project space and collective based in part of Rovereto train station in Italy with a wide range of participants including artists, food projects, designers, scientists and others. We visited the project and spent time with the members. We held workshops with the members to generate visual material which was integrated into an adaptive identity system. As part of our ongoing collaboration with La Foresta, we published a short piece together for the Journal of Aesthetics and Protest.

> Wouter reads:

Evening Class asks La Foresta asks Evening Class:

One of our main impressions from spending time here is the sense of abundance – people are so generous with their time, attention and resources. What role do you think generosity plays in creating a space like this?

La Foresta responds = There is a saying in synergic gardening that “we fertilise each other”. The social relations between us are the most important thing we have, and need to be cultivated and safeguarded, while material resources come and go. We want to build up an environment in which everyone feels free to contribute to the Forest according to their own resources and will, without feeling guilty for giving too much or too little.

Once COVID hit, it became difficult to continue our program in the same way. A lot of how we worked had operated around being in the same place, which was now not possible. ECembling was one response to this – we decided to create a publication made of A3 pages independently designed and printed by our members, which were then assembled into a final publication, with all funds going to the ‘Artists fund Artists’ campaign supporting black artists in the UK.

Like many others during the lockdown we got pretty tired of online meetings and felt disconnected due to inability to plan any of our activities. To get through it, we started a meditation class led by a guest from Croydon Buddhist Centre. We read and discussed some of the Buddhist texts and it made us think about our boundaries of care and how far they extend.

When thinking about design and care we came across this Mark Fisher quote, which summed up quite neatly a lot of the things we had been working through as a group:

> Wouter reads:

Yeah, but is “community” the right term for it? I have a lot of problems with the term “community”, largely because of the way it’s been easily appropriated by the right. But also, because it implies an in and an out. Some are in the community and some are out of it. I had a slogan once: “Care without community”. Isn’t that what we want? Where you can give people the care regardless of whether they belong to the community.

Any mutual aid or self-organised group like ours has limitations – only those who have the time can participate, there’s no student loans available to continue your education like this, we have no mental health provision, or sport facilities, or studios. We try and connect with groups with shared interest and act in solidarity, and make more space for care. We’ve always operated with the principle of trying to not take up too much space, keeping everything open source, and hoping that those who might be interested in what we do might find and use some of our work if it might be useful. But in reality, there’s a limited amount a small group operating outside working hours can achieve.

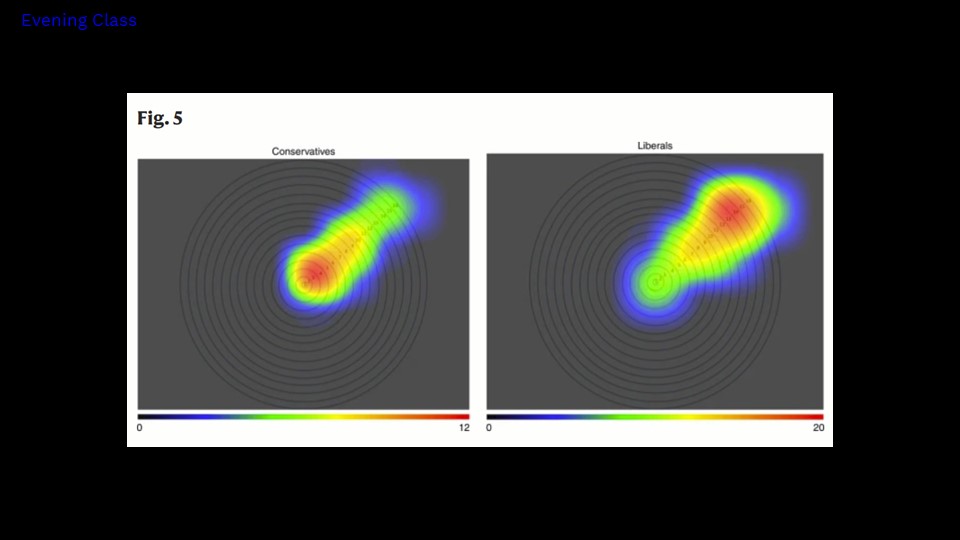

On this topic of boundaries or care, and who is in and who is out of the community, we also came across this study, published in Nature journal. It shows who participants state they feel empathy with. In the centre of the circle is the self, followed by immediate family, close friends acquaintances, all the way out to inanimate objects. For a significant number of people, care does not exist beyond their own front door. How are we supposed to live with that? I think that is our next question.